“People only remember your weird.” — George Mack

Last Friday night, I wanted a place to find charts that aren’t boring as hell.

I use them all the time for the jAI newsletter, but couldn’t find one…

So I built it.

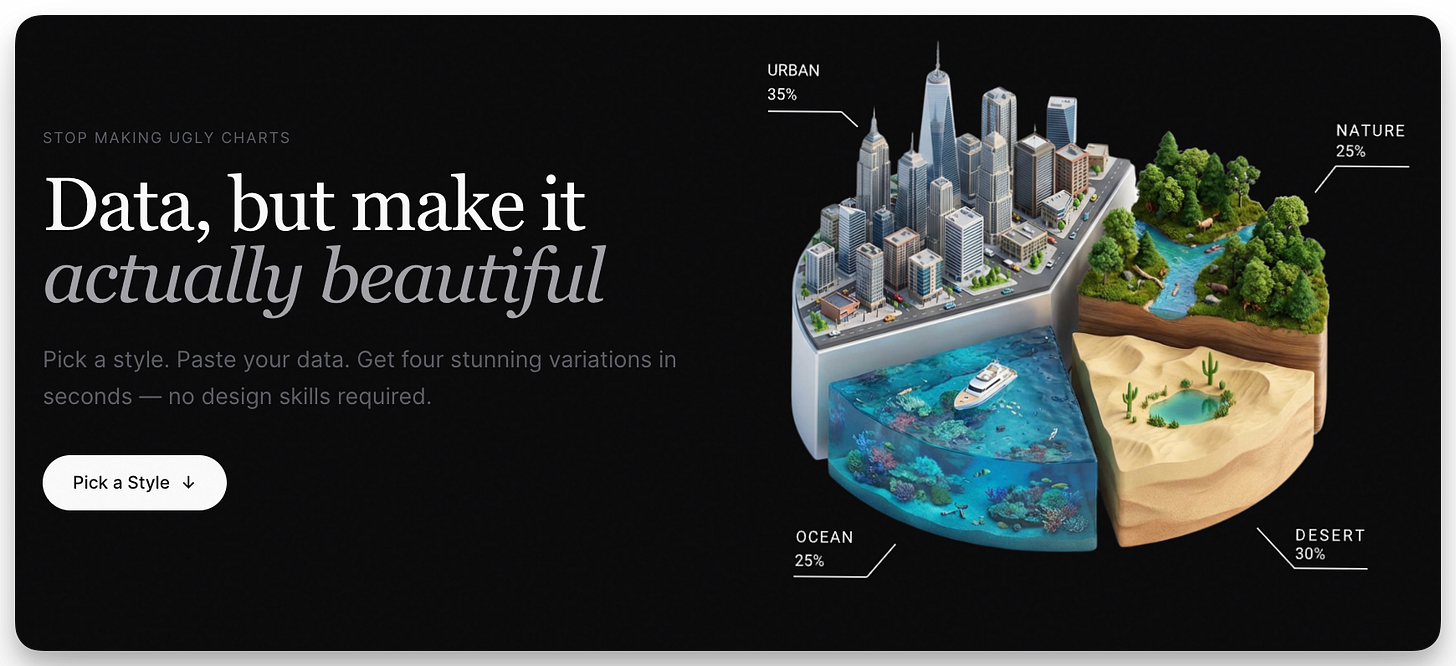

By Sunday, I had Chart Studio AI.

A working site where you paste your data, pick a style, and get back something that doesn’t look like it was made in Excel in 2007. Woodcut charts. Comic book charts, hand-drawn napkin sketches. The whole thing came together in a weekend.

But here’s the thing…

I didn’t set out to build anything connected to my actual work. I just wanted cool charts.

And look at what showed up anyway.

A random owl mascot. (Why an owl? I don’t know. I just wanted an owl.)

Error text that says “Whoa there, Picasso.”

A blog section with articles like “The Con Man Who Invented the Pie Chart.” Because how do you make data visualization interesting? You tell the story of the criminal who created it.

None of this was best practice. None of it was necessary. All of it was a signal.

The Luckiest Era

We live in a strange time.

Building used to require permission. Capital. Teams. Months of planning. If you wanted to make something, you had to know what you were making before you started. The cost was too high to “figure it out” as you went.

That’s over.

You can build a working product on a weekend now. With AI. With no-code tools. With whatever you have lying around. For me, the barrier has dropped so far that building stopped being a decision and became a reflex.

The old model: Think first, then build.

The new model: Build first, then think.

When there’s nothing on the line except your time, you can build loose. Follow what’s interesting. Let it be weird.

That’s when you learn what you’re actually drawn to.

And that’s when you build something that could only come from you.

Let it be weird.

That’s when you learn what you’re actually drawn to.

And that’s when you build something that could only come from you.

When Best Practices Are Worst Practices

Here’s advice you won’t find in a LinkedIn carousel.

If you want to discover what makes you different, the worst thing you can do is build “correctly.”

I wrote last week about defaults, the invisible settings that shape your behavior before you even make a choice. Best practices are the defaults of your space. The expected way things look, sound, and work. The templates everyone follows without questioning.

Every space has them.

Data visualization tools are supposed to look like enterprise software.

Clean logos.

Stock photos of people pointing at charts in meetings.

Blog posts titled “5 Best Practices for Effective Data Visualization.”

Error messages that say “Invalid input. Please check your data format.”

The owl, the Picasso line, the con man article…none of it belongs in a data tool. That’s why it’s a signal.

When I built it, none of these felt like bold creative choices. They just felt like what the thing wanted to be. The owl showed up. The Picasso line made me laugh. The con man article was interesting to me, so I wrote it.

So why does the weird stuff feel so natural when you’re making it? Jay Acunzo spent years trying to figure that out. (His book Break the Wheel is the best thing I’ve read on this.)

The difference, he found, is always context. Best practices strip out the specific details of your situation and replace them with generalized wisdom that worked for someone else, somewhere else, at some other time. Without your context, you’re making decisions that are “close enough.” And close enough leads to work that is, at best, good enough.

When you follow the defaults, you’re invisible. Not because you’re bad. Because you match expectations perfectly, and the brain skips right over things that match expectations. You don’t notice defaults. That’s what makes them defaults.

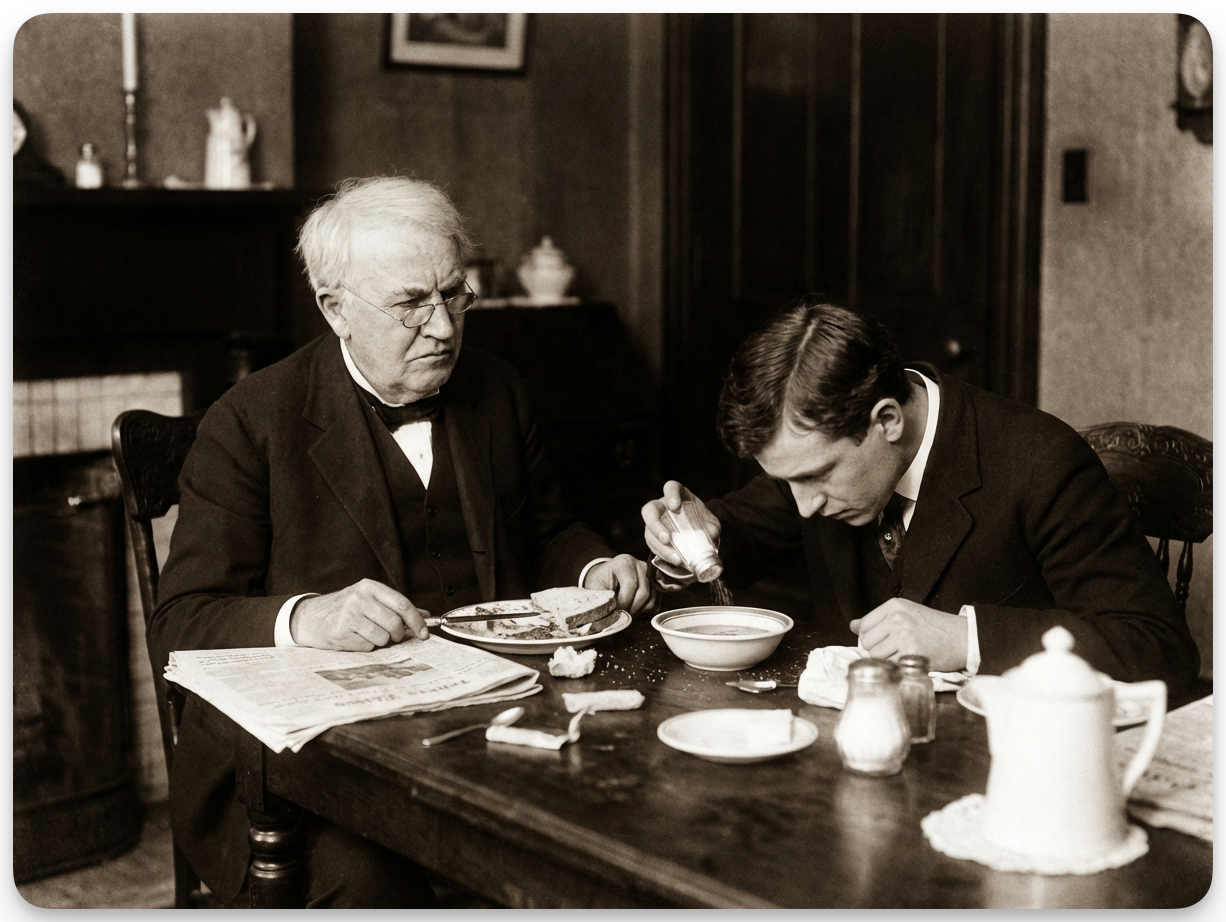

There’s a story about Thomas Edison that captures this perfectly.

When interviewing candidates for his research lab, he’d take them out for a meal and order soup. Then he’d watch. Anyone who salted their soup before tasting it was rejected on the spot.

Edison didn’t want people who made assumptions before collecting data. He wanted people who tasted first, then decided what the soup needed.

Best practices are salt before you taste. You’re seasoning your work with other people’s preferences before you’ve even discovered your own.

Derek Sivers has a phrase for the invisible force that makes us do this anyway: The Invisible Jury. We build as if a panel of professionals is watching and scoring our decisions. We add what we think they’d approve of. We remove what might make them raise an eyebrow.

The jury doesn’t exist. But we perform for it anyway.

But your expertise is shy. It doesn’t announce itself. It sneaks into the unexpected additions, the “why did I even include this” details, the stuff you almost removed because it wasn’t professional enough.

That’s where you live. In the moments that break the defaults.

Close enough leads to work that is, at best, good enough.

The Cost of Fitting In

Here’s what’s interesting about this.

Jonathan Courtney runs AJ&Smart, a design consultancy that works with some of the biggest banks and corporations in the world. The clients most people assume want buttoned-up professionalism.

He recently spoke at a conference in Oslo. Instead of slides, he did an improv session. There was music. He reviewed chocolate on stage. The whole thing was modeled after a stand-up comedy set.

“If I had to go up there and do slides and just do it in the way everyone else was doing it,” he said on his podcast, “it really would make me feel depressed. It would make me feel like this is pointless.”

When you edit out the weird stuff, you don’t just lose signal. You lose energy. You lose the feeling that the work is yours. You start to wonder what the point is.

But here’s where it gets fun for anyone worried that being weird costs you clients.

Courtney’s team faces pressure constantly. A new employee joins, sees something “weird” in the brand, and says, “We should take that out because that’s not going to be okay for the corporation.” They keep it in. The corporations are also humans. They also might find it funny.

And the result? Those same companies keep booking them.

“Other CEOs see me doing this, and they’re like, ‘that wouldn’t work for my clients,’” Courtney said. “Our clients are all the biggest banks and corporations. The clients you want? They’re watching, and they’re booking us. You just don’t get it. People can tell that we are being real. And that’s the thing that becomes attractive.”

The weirdness isn’t a liability. It’s the protection. Especially now, when AI can generate anything generic in seconds, the stuff that’s unmistakably you is the only stuff that stands out.

And here’s the part that should make you uncomfortable: that instinct to remove, to smooth over, to professionalize? That’s the same instinct that would have killed the owl. The con man article. The “Whoa there, Picasso.”

Best practices don’t just hide your patterns from others. They hide them from you.

The weirdness isn’t a liability. It’s the protection. Especially now, when AI can generate anything generic in seconds, the stuff that’s unmistakably you is the only stuff that stands out.

What Chart Studio Revealed About Me

I didn’t realize until later that the whole project pointed somewhere.

Making invisible things visible. (Data into beautiful charts.) Personality in utility. (The owl. The jokes.) Making boring things interesting. (Criminal history of pie charts.)

These patterns have nothing to do with data visualization. They have everything to do with what I actually care about.

A week after I built Chart Studio, I started sketching Framework Studio. A tool to help people visualize their methodologies. Take the invisible thing in your head and make it something you can see.

The connection was obvious. Once someone else pointed it out.

I built a fun weekend project. My patterns leaked into it. And now I can see something I couldn’t see before.

How to Read What You’ve Already Built

You’ve probably already made things. Side projects. Abandoned apps. That thing you built for yourself that no one else uses.

Run these questions against any of them:

1. What did you add that wasn’t required? The decoration. The personality. The thing that made you smile but served no functional purpose.

2. What problem were you actually solving for yourself? Not the stated problem. The real itch. Why did THIS bother you enough to build something?

3. What would you have kept even if no one ever saw it? If this project stayed private forever, what parts would still matter to you?

4. What does this have in common with the LAST random thing you made? The throughline. The pattern that keeps showing up. The thing you can’t seem to stop caring about (AI is REALLY good at helping with this.)

5. What did you almost remove because it wasn’t “professional”? That’s probably the most revealing part. The weird stuff IS you. Everything else is costume.

The Honest Part

Here’s what I have to admit.

I built Chart Studio. The patterns were there. But I didn’t see them clearly until a client said:

“What in the world were you thinking when you built this?”

Until I talked it through in a conversation that wasn’t about Chart Studio at all.

The artifact revealed the pattern. Reading the pattern still took another set of eyes.

Derek Sivers puts it simply: “Obvious to you is amazing to others.” The things you added without thinking, the details that felt unremarkable, the choices you almost didn’t mention because they seemed too obvious? Those are exactly what someone else would find fascinating.

The problem is you can’t see them. Not because they’re hidden. Because they’re too close.

Building generates signal. But reading signal is a different skill.

And reading your own signal might be the hardest version.

So build things. Let them be weird. Stop editing out the unnecessary. Your patterns will show up whether you’re looking for them or not.

And if you can’t see what they mean?

Find someone who can. Or use the tools I built for exactly this.

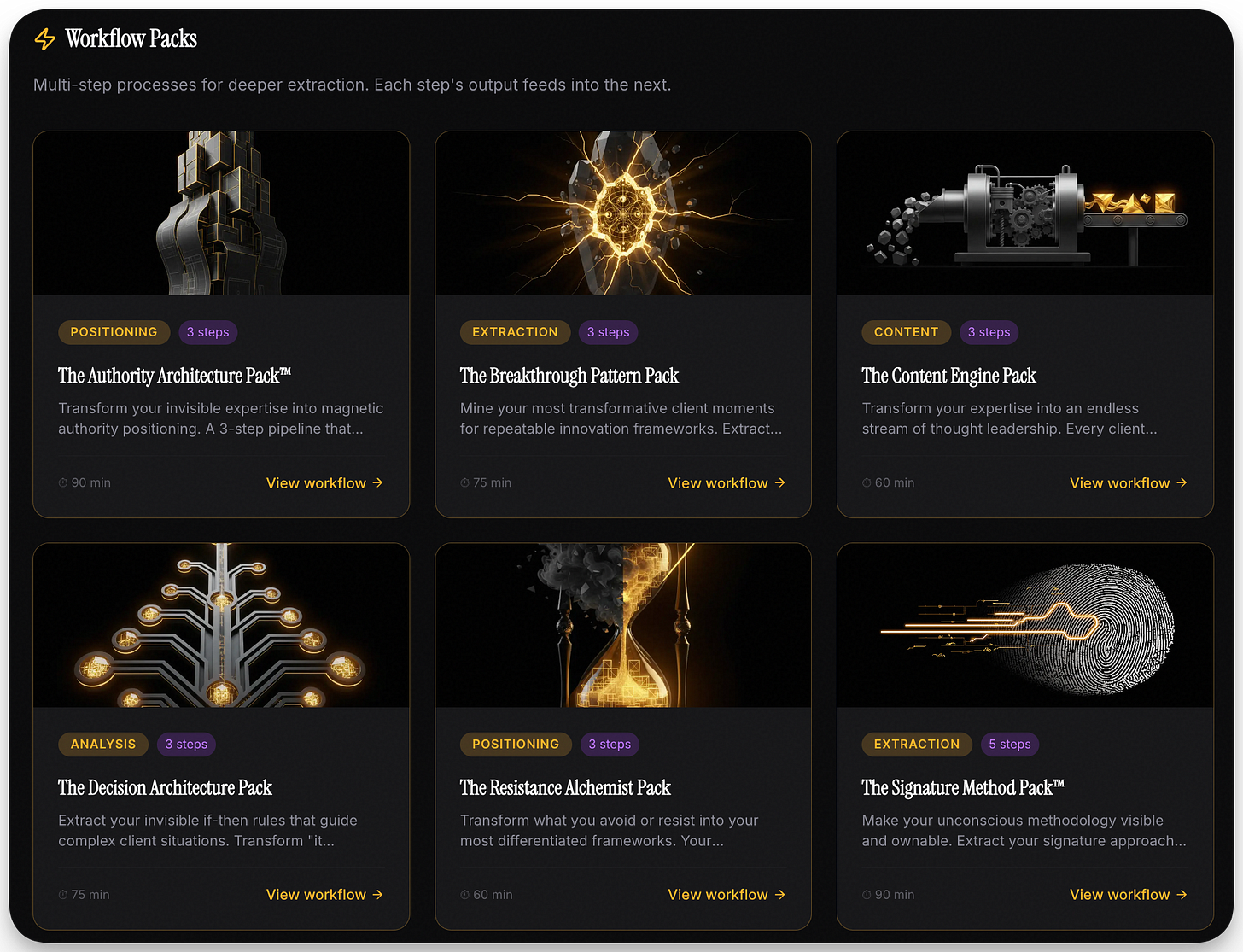

For Paid Subscribers: The Three Lenses Prompt

I mentioned that reading your own signal is the hardest version. So I built something.

The prompt below runs your raw material through three lenses designed to surface what’s hidden:

Edison finds assumptions you’re making without realizing (the salt you added before tasting)

Sivers spots what’s obvious to you but fascinating to others (the invisible jury you’ve been performing for)

Acunzo identifies your unique context that makes “best practices” wrong for you

The output: 2-3 concrete project ideas with the differentiation already baked in.

You probably have material sitting in folders right now. Transcripts from client calls. Voice memos you recorded while driving. A draft that’s been “almost done” for three weeks. The ideas are already in there. They’re just hiding in a throwaway line you almost deleted.

This is the prompt that finds them.

What You Get With Paid Access

This prompt is part of The Cognitive Fingerprint Prompt & Workflow Library. When you upgrade, you get password access to the full library on my site. These are the same prompts and workflows I use with clients, yours to use immediately.

What’s inside:

Expertise extraction prompts (surface patterns you can’t see)

Framework identification workflows

“Hidden genius” diagnostic tools

Decision-making pattern extractors

Voice and communication style analyzers

New prompts and workflows added weekly

Also included:

The Expertise Blindspot Finder GPT ($99 value) — Paste in a transcript, get your hidden patterns back in minutes

The Framework Factory Course ($497 value) — The complete system for transforming invisible expertise into documented IP

Deep dives into the methodology

Real extraction examples from actual client work

“I have used two of these prompts, and came away impressed.” —Bonnie

“I found this to be very on point, I recently went through a pitch call that I just couldn’t describe my value in the most effective manner. This was timely and spot on. I have used two of these prompts, and came away impressed.” — Tyler

“That’s bang on. That’s all me.” —Lou

The Price Goes Up Monday

This is the last week to get in at $10/month.

Starting December 22nd, it goes to $20/month.

If you’ve been thinking about it, this is the week. One extraction that helps you win a single deal covers way more than the entire year.

And I will even sweeten the pot for you - if you upgrade, I will help create a custom prompt for you to do just that…but just until Monday 12/22.

Subscribe Now — $10/month (price doubles Dec 22)

Already a paid subscriber? The prompt is below.

The Three Lenses: Turn Raw Material Into Something Uniquely Yours

What This Is

You have raw material sitting in folders. Transcripts from client calls. Voice memos you recorded while driving. A draft that’s been “almost done” for three weeks. Notes from a brainstorm session that felt important at the time.

The material knows what it wants to become. You don’t.

This is the part I find fascinating: the best ideas are usually already in the document. They’re just hiding in a throwaway line you almost deleted, or buried in a tangent you thought was off-topic. Your brain skipped right over them because they seemed too obvious to mention.

This prompt runs your material through three lenses, each designed to surface what’s hidden:

Edison finds assumptions you’re making without realizing (the salt you added before tasting)

Sivers spots what’s obvious to you but fascinating to others (the invisible jury you’ve been performing for)

Acunzo identifies your unique context that makes “best practices” wrong for you

The output: 2-3 concrete project or asset ideas with the differentiation already baked in.

How to Use It

Step 1: Find your raw material

Dig up that transcript sitting in your Otter.ai account. The Google Doc with 47 comments from yourself. The voice memo from last Tuesday that you still haven’t listened to. It’s probably in a folder called something like “To Process” or “Ideas” or “Stuff.”

Step 2: Copy the prompt below into Claude (or your preferred AI)

Step 3: Upload or paste your material when asked

Step 4: Get back project ideas that only YOU could build

The whole thing takes maybe 10 minutes. The material does most of the work.

What You’ll Walk Away With

Not vague inspiration. Specific outputs:

The assumptions baked into your thinking that you didn’t know were there

The throwaway lines that are actually your most interesting ideas

The context advantages you’re not leveraging (what only YOU could build)

2-3 concrete project ideas with the weird angle already defined

Clarity on who each idea serves and what job it does for them

The ideas were already in your material. The lenses just make the introduction.

What I Got When I Ran It

I fed this prompt a transcript from a recent conversation with a colleague. One of the ideas it surfaced:

Founder-to-Team Knowledge Transfer System

A focused offering for founders who need to get what’s in their head into their team’s hands. You take their existing transcripts (calls, meetings, trainings) and produce a library of training cards. Each card captures one pattern, principle, or protocol they use. The output isn’t a full methodology extraction. It’s a systematized training library their team can actually use.

Who it’s for: Founders who keep explaining the same things to their team. Leaders who’ve become the bottleneck because decisions stall when they’re unavailable.

The differentiation the lenses surfaced:

Edison spotted the assumption that training materials need to be created from scratch. They already exist in transcripts. They just need extraction and formatting.

Sivers elevated something I mentioned casually in passing. It wasn’t “pull out patterns.” It was “build a searchable library of how you think.”

Acunzo connected it to my “extract vs. create” philosophy. I’m not writing training content. I’m excavating it from what already exists.

The weird angle: “Training manuals from transcripts, not from scratch.”

Here’s what’s interesting: I’d mentioned the training card idea offhand in the conversation. Didn’t think much of it. The prompt caught it and showed me why it was more valuable than I realized.

I’m probably going to build this.

Prompt below the paywall or in the new library: